“Father,” Tilo called again to his father from across the long table. The old man paused and looked up from the pile of papers before him. Fixing a metallic gaze upon his dwarf son as if he were surprised he could speak at all, the baron got up and walked to the fireplace.

“What is it, Tilo?” The old man enquired momentarily, bending down to add more logs into the dying embers and driving the chill out of the room as the shadows retreated to the corner from the now merry flame.

“Now that my brother, Deli, has joined the monastery I want what is rightfully mine.” There, he said it. Tilo had been preparing for this moment for a fortnight now, ever since his brother left for the monastery. Tilo was born the second son to the baron and had been abhorred from birth due to his stature. A dwarf, with a large head and a brute face accentuated by his protruding brow, his twisted stunted legs made his movement awkward as he wobbled when he walked. He was conscious of his stature but more so whenever he was around his father, Baron Kesi, who never made him forget what he was.

Turning slowly to face his son, the baron stood straight back without saying a word for a long time, boring into his son with his golden eyes. The reflection from the flame made his eyes glow like chips of fire, and Tito felt uncomfortably aware of his hanging legs seated on the high chair, and his twisted back. But defiantly, he held his gaze. He had learned to be defiant from a young age, otherwise, he wouldn’t have his way.

“You,” he said slowly as if savouring the word, bile dripping from his voice. “You who killed his mother at birth, You whom the gods gave to humble me, dragging my mane into the gutter with your abominable existence. I allow you to wear my Sigil, and have the name of my family, which my forefathers fought to exalt above other houses with sword and fire.

“Every day I watch you saunter and cackle around, suffering your debauchery for this is the punishment the gods have given me. But, no laws of man or God will ever make me surrender my estate to you. You will do your duty and when the time is right, you will have a reward worthy of your station.”

Tilo felt extremely cold all over and his chest felt tight like an iron grip. He couldn’t speak, just stared at the man he called his father with disbelief. “I didn’t wish to be born this way, father….” he began.

“Hush, don’t call me that. Be grateful you were born into this family, not a peasantry where you’d be thrown to the dogs at birth, for what you are. Now, get up and never come to my presence unless I summon you. No more word about what is rightfully yours or you’ll be banished. Down to the gutter like the rat you are, make sure the drains flow better or I’ll have you mucking the stables.” And with that, he turned back to the fire and stood staring into the flames.

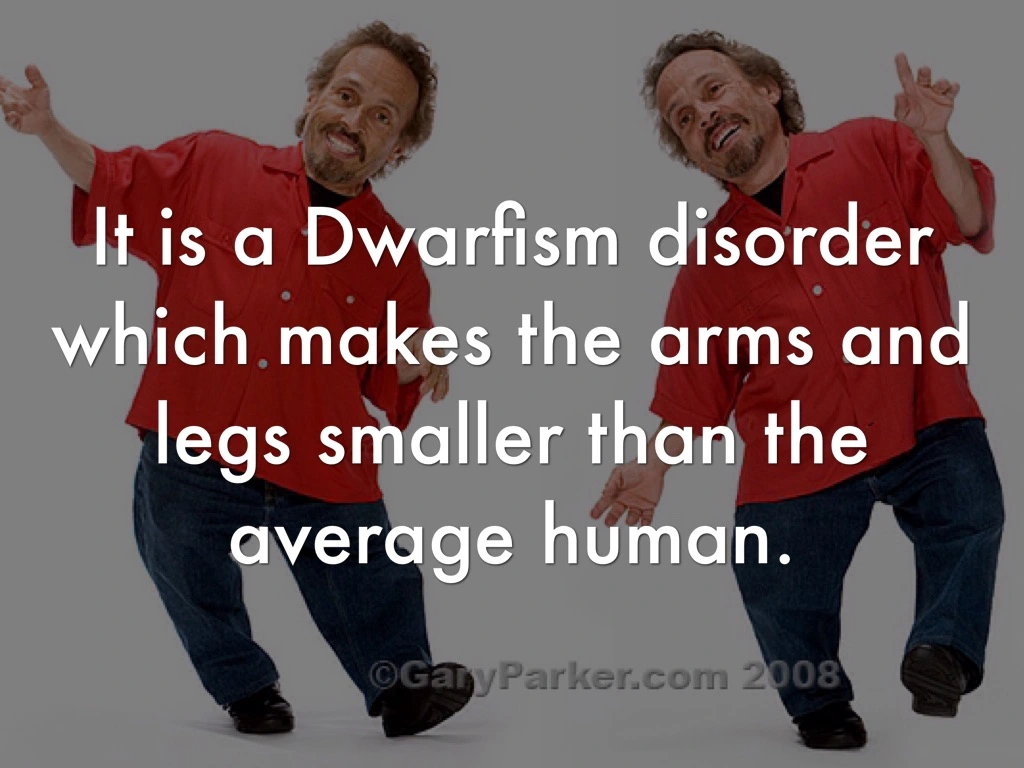

Dejected, Tilo wriggled to the flow and grabbed his walking stick. He stood momentarily on the spot looking at his father’s back before slowly wobbling out of the great hall. Tilo had been born with a genetic disorder that had impeded his growth, resigning him to dwarfism. This condition is the result of achondroplasia. Achondroplasia is a rare genetic disorder that causes short stature and bowed legs.

Tilo had difficulty walking due to his bowed legs, leading him to have the staff aid him. People with achondroplasia can also develop lumbar spinal stenosis as a result of abnormal bone growth. This condition causes a compression of the nerves in the spine, leading to pain, weakness, and mobility problems. It is a serious complication and the leading cause of later-life disability in people with achondroplasia.

Reaching the feet of the stairs of his lodging, Tilo cursed at the impending climb. He was sleepy having not slept very well through the night. He was a restless sleeper who rarely made it through the entire night. Research shows that achondroplasia also causes sleep apnea. When a person has sleep apnea, their breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep, which can result in low levels of oxygen. Symptoms include daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, restless sleep, and more.

Achondroplasia can be inherited, as parents pass genes to their children. When a parent has a mutation in the FGFR3 gene, there is a possibility of passing it to their offspring, potentially resulting in the child developing the condition. Despite this, achondroplasia remains rare; a 2020 review indicates that approximately 80% of individuals with achondroplasia have parents of average stature, who have a very low likelihood of having another child with the condition.

The genetic dynamics become more complex if one or both parents have achondroplasia. If both parents are affected, there is a 25% chance their child will have average stature, a 50% chance the child will inherit achondroplasia and a 25% chance the child will have homozygous achondroplasia, which is fatal in infancy.

Various genetic factors can influence the likelihood of developing achondroplasia. Notably, paternal age plays a significant role; fathers over 34 years old have an increased chance of having children with the FGFR3 gene mutation, even if the parents do not have achondroplasia. Research indicates that approximately 1 in every 15,000 children is born with achondroplasia. This risk rises sharply for children of older fathers, with 1 in every 1,875 children born to fathers over 50 years old developing some form of skeletal dysplasia, a group of conditions affecting bone and cartilage cells, including achondroplasia. It remains uncertain whether other factors also influence the likelihood of developing achondroplasia.

Achondroplasia is a rare genetic disorder that impacts bone growth, leading to difficulties in walking and reaching. Individuals with achondroplasia can transmit the genetic mutation to their offspring, although many children of affected parents do not inherit the condition. The likelihood of a child developing achondroplasia increases if the father is over 35 years old at the time of the child’s birth.