NAIROBI — Each dawn in Dandora, the smoke begins to rise. From the sprawling dumpsite on the city’s eastern edge, thick grey clouds drift across the sky, seeping into homes, classrooms, and market stalls. The acrid haze clings to the air long after the fires die down. For children walking to school, every breath carries an invisible risk.

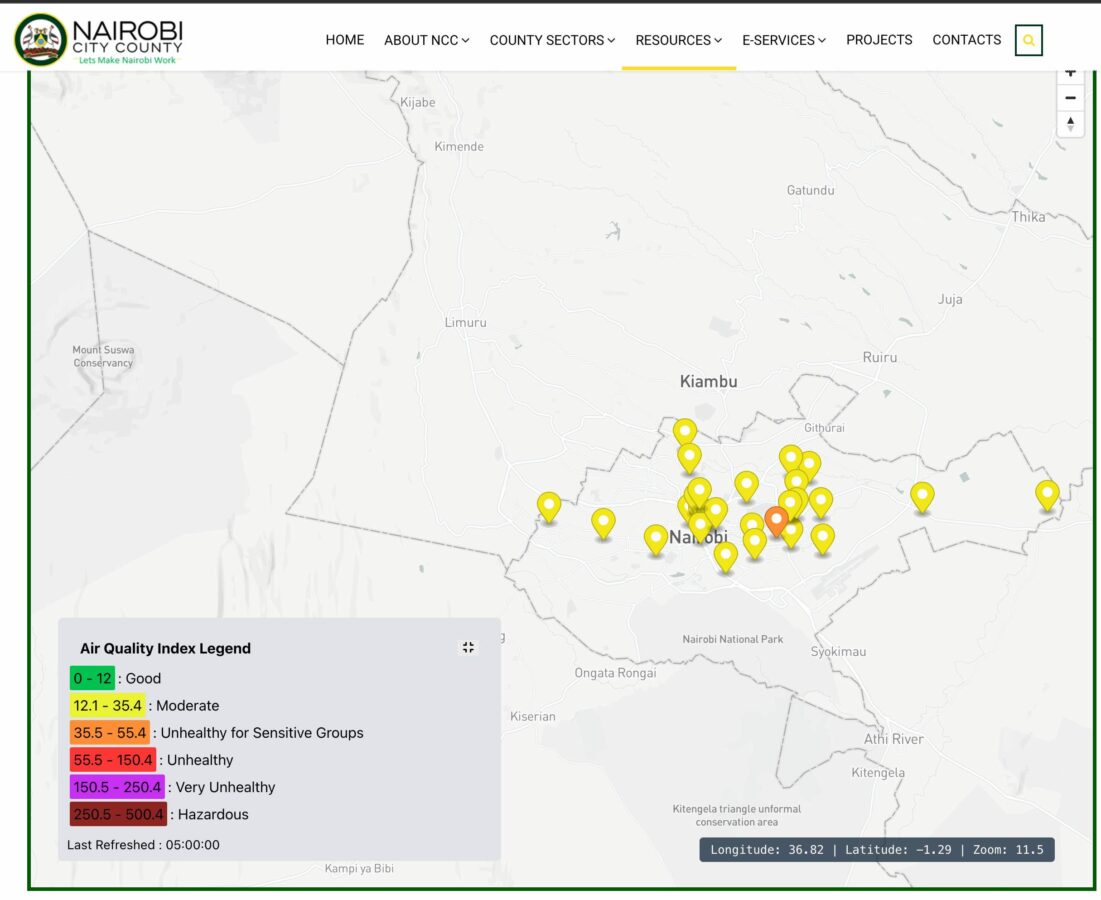

This is one of Nairobi’s pollution hotspots, now under the watch of newly installed air quality monitors. The city has begun rolling out 50 sensors across its most vulnerable neighbourhoods—places where exhaust fumes, burning waste, and dust have turned the simple act of breathing into a daily hazard.

The network stretches from Eastlands to major traffic corridors like Thika Road and Mombasa Road, where endless streams of matatus, lorries, and private cars pump black smoke into the air. Here, fine particles known as PM2.5 hover at levels far above what health experts consider safe.

At Mama Lucy Hospital in Kayole, doctors have long noticed a pattern. Children from nearby estates often arrive wheezing, their lungs strained by constant exposure to polluted air. Now, with two advanced monitors perched on the hospital’s roof, they can match the cases they see with the data outside. “We finally have proof of what we have lived with for years,” said Dr. Martin Wafula, the hospital’s CEO.

Downtown Nairobi tells another story. At rush hour, Kenyatta Avenue and Haile Selassie Avenue become rivers of idling vehicles, their fumes trapped by tall buildings. Air monitors here reveal sharp spikes in pollution during the morning and evening commute.

For residents of Mukuru kwa Njenga, one of the city’s largest informal settlements, the danger comes from closer quarters. Charcoal stoves and kerosene lamps fill cramped rooms with soot. Combined with nearby industrial emissions, the air is a cocktail of pollutants. A new sensor here is already recording levels that alarm health officials.

City authorities, working with international partners, say these monitors are just the beginning. More are planned for Gikomba, Kariobangi, and other industrial hubs where factory smoke and waste burning remain unchecked.

The data, officials hope, will force a reckoning. “Air pollution is not just an environmental issue—it is a public health emergency,” one county environment officer told reporters.

For now, Nairobians continue to inhale what surrounds them. In Dandora, children still play under the smoke-stained sky. In Mukuru, families light evening fires in rooms with no ventilation. And on Mombasa Road, thousands of commuters drive through a daily fog of exhaust.

The monitors may not clear the air, but they shine a light on what too many Nairobi residents already know: the city is breathing on borrowed time.

In pockets across Nairobi, a quiet revolution is unfolding. Small air-monitoring devices, perched atop lamp posts and hospital rooftops, are churning out real-time data—offering the city its first crystal-clear view of the pollution that chokes its air.

The effort is part of a broader push, led by Nairobi City County and global partners such as the Clean Air Fund, C40 Cities, and USAID, to confront a growing health crisis. In June, the city launched its first city-owned network, deploying 50 sensors to pinpoint pollution hotspots and guide urgent action to protect public health.

At Mama Lucy Hospital, two advanced monitors now track PM2.5 fine particles, black carbon, humidity, and wind—clues that paint a vivid picture of the air residents breathe. High concentrations of these particles are linked to respiratory ailments. “These monitors allow us to track where patients are coming from,” noted Dr. Martin Wafula, the hospital’s CEO. “Now we can target interventions to the areas that need it most.”

These are not just pieces of equipment—they are lifelines for communities near dumpsites and busy roads. In Dandora, where smoke from burning rubbish fills classrooms each morning, sensors helped confirm air quality levels well above safe limits. In response, students at a local secondary school began planting bamboo—nature’s air filter—to soften the toxic haze they inhale each day.

The city has also installed regulatory-grade monitoring stations at Mama Lucy and the Nairobi Fire Station, thanks to the Clean Air Catalyst project, with plans for around 37 more sensors covering every ward.

For the first time, Nairobi has the data it needs to fight back. And as one official put it: “Improving air quality in African cities begins with knowledge and data.”